Werner06.LossLAE

Reading: BASIC RATEMAKING, Fifth Edition, May 2016, Geoff Werner, FCAS, MAAA & Claudine Modlin, FCAS, MAAA Willis Towers Watson

Chapter 6: Loss and LAE

Contents

- 1 Pop Quiz

- 2 Study Tips

- 3 BattleTable

- 4 In Plain English!

- 5 POP QUIZ ANSWERS

- 6 Data Aggregation Example

- 7 Pop Quiz A - Answer

Pop Quiz

Study Tips

BattleTable

Based on past exams, the main things you need to know (in rough order of importance) are:

- loss trend

- trended ultimate loss

- benefit change

reference part (a) part (b) part (c) part (d) E (2019.Fall #5) loss trend

- AY factorloss trend

- PY factoroverlap fallacy

- trend vs developmentE (2019.Fall #6) reinsurance

- in ratemakingWerner07.OtherExpenses Werner07.OtherExpenses E (2019.Spring #4) loss trend

- basic limitsloss trend

- excess limitsloss trend

- total vs basic limitsE (2019.Spring #5) trended ultimate loss

- calculateexcess loss threshold

- capping shock lossesE (2018.Fall #5) loss trend

- 2-step procedureE (2018.Spring #5) Excel Practice Problems E (2017.Fall #06) benefit change

- direct effectbenefit change

- indirect effectE (2016.Fall #4) trended ultimate loss

- calculateimpact of a change

- lower claim countsimpact of a change

- fewer high deductiblesE (2016.Fall #5) reinsurance

- net trended pure premiumE (2015.Fall #4) loss trend

- for pure premiumE (2015.Fall #5) benefit change

- loss adjustment factorbenefit change

- loss adjustment factorloss trend

- comment on selectionE (2015.Spring #8) excess loss

- calculate factorexcess loss

- calculate ultimateE (2014.Fall #4) benefit change

- direct effectbenefit change

- indirect effectE (2013.Fall #5) trended ultimate loss

- large loss adjustmentlarge loss adjustment

- appropriate?rate analysis

- suggest modificationsE (2013.Spring #7) trended ultimate loss

- calculateE (2013.Spring #8) trended ultimate loss

- calculate

In Plain English!

Intro to Losses

This intro is almost exactly the same as the intro to Chapter 5 - Premium. In that chapter, we learned how to restate raw premium data from the historical period to the effective period. We did this using the concepts of current rate level, trending, and premium development. In this chapter we're going make analogous adjustments losses.

Recall the Fundamental Insurance Equation:

- premium = (Losses + LAE + U/W Expenses) + U/W profit

This is the insurance version of the basic formula price = cost + profit, where cost equals the term in parentheses. In this chapter, we focus on the Losses portion of the equation. The goal in a pricing analysis is to determine the losses the insurer expects to have to pay out due to future claims. if we simply use raw loss data in our analysis our conclusions may be wrong. Here are 4 specific items that can impact our loss data:

- extraordinary losses

- → to account for this...

- coverage and benefit levels

- → to account for this...

- development of losses

- → to account for this...

- trends

- → to account for this...

Loss Definitions

We covered the basic loss definitions in the reserving material. For a review, including a web-based practice problem, see Reserving Chapter 2 - Basic Formulas. The concepts are the same in the pricing material but there are small differences in terminology between the reserving and pricing source texts:

- The dollar-values an insurer pays out can be called either claims (according to the reserving text) or losses (according to the pricing text).

- reported loss = (paid loss) + (case reserves)

- → case reserves is the same thing as case incurred loss which is sometimes just shortened to incurred loss

- → case reserves is called case outstanding (or case O/S) in the reserving text

Alice has a quick reminder for you, because it's something you've got to be totally clear on:

- for an individual claim:

- → reported loss = (paid loss) + (case reserve)

- for a set of claims over a given time period such as a CY:

- → CY reported loss = (CY paid loss) + (change in case reserve)

(If you're in the exam and you're rushing it's easy to mess this up.)

Loss Data Aggregation Methods

Data aggregation methods have already been discussed. Click the links below for a review.

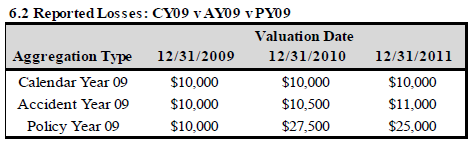

There's a good example from the source text where you're given a claims transactions history and you have to calculate the CY, AY, and RY for reported losses at 3 different valuation points: 12/31/09, 12/31/10, and 12/31/11. Give it a try. Click for Answer

Common Ratios Involving Statistics

The source text states:

- Four common ratios involving loss statistics are: frequency, severity, pure premium, and loss ratio. As stated previously, each ratio is defined by a choice of relevant statistics (e.g., paid or reported losses, or earned or written premium), a data aggregation method (e.g., calendar, accident, policy, or report month/quarter/year), an accounting period, and a valuation date.

We have already covered this material. For a review, including a web-based practice problem, see Pricing Chapter 1 - Basic Insurance Ratios.

Adjustments to Losses: Extraordinary Losses

Large Individual Losses

Large individual losses, also called shock losses, happen infrequently but can cause instability in the ratemaking process. An example may be the permanent disability of a young worker due to complications from COVID-19. A ratemaking analysis using a historical experience period containing a shock loss may suggest the need for a large rate increase, but given the infrequency nature of such losses, it would be better to spread the effect over a longer period to reduce volatility in rates.

Question: what is the general procedure for dealing with shock losses in ratemaking

- remove losses above a certain threshold

- replace with an average expected large loss amount

Question: how can a shock loss threshold be determined

- in general:

- • maximize number of losses included

- • minimize volatility in the ratemaking process

- in general:

- specific choices may include:

- • basic limits amount included in a standard policy

- • reinsurance limit

- • percentage of coverage amount

- • 99th percentile of size-of-loss distribution

- • industry benchmark

- specific choices may include:

Let's look at a numerical example. As always, we'll start with something very easy then build to something more complex. The key concept is the excess loss factor, also called the excess ratio.

excess ratio = (losses in excess of threshold) / (non-excess losses)

Suppose we have an individual claim of $105,000 and our shock loss threshold is $100,000. Then the excess ratio is 5,000 / 100,000 = 5%. Simple.

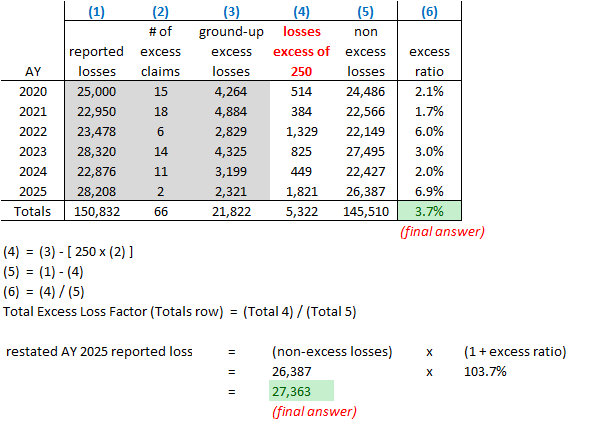

Let's now consider the more complex example below where we have many claims across 6 separate accident years and the large loss threshold is 250. The excess loss factor (excess ratio) in column (6) can vary considerably from year to year so we'd like to smooth it using a multi-year average of excess losses. In the example below, the multi-year average is 3.7%. (In practice, the multi-year average should certainly use more than 6 years but the method is otherwise the same.)

The restated AY 2025 reported losses is 27,363. The first 3 shaded columns are the given information and columns (4), (5), and (6) are calculated from the given formulas.

The quiz has a web-based practice problem similar to the above example.

mini BattleQuiz 1 You must be logged in or this will not work.

Catastrophe Losses

Shock losses are individual high severity claims. (See previous section.) Catastrophes are characterized more by a high frequency of claims, due to natural or man-made disasters such as hurricanes, earthquakes, wildfires, and many others. The total losses from a catastrophe may be high even if individual claims are not.

Catastrophe losses are treated similarly to shock losses. They are removed from the data and replaced with an average expected catastrophe loss amount. There's an example in Appendix B - Homeowners Indication but for now here's an overview.

Question: identify 2 methods of analysis for catastrophe losses in ratemaking

- non-modeled catastrophe analysis

- catastrophe models

Question: identify scenarios where each type of catastrophe analysis is likely to be used in a ratemaking analysis

- non-modeled catastrophe analysis

- for events that happen regularly over a period of decades (Ex: hail storms for personal auto)

- non-modeled catastrophe analysis

- catastrophe models

- for infrequent events with very high total losses (Ex: hurricanes, earthquakes)

- catastrophe models

Recall that for shock losses, the excess loss factor was calculated as the ratio of (excess losses) to (non-excess losses). A non-modeled analysis works the same way. For the hail storm example, you would calculate the ratio of (hail storm losses) to (non-storm losses) over a 10-30 year period, the time frame being judgmental based on the data. Appendix B - Homeowners Indication discusses a pure premium approach and looks at the long-term ratio of catastrophe losses to exposure.

Pop Quiz A! :-o

- If an insurer's concentration of exposures in the most hail-prone area of a region has increased drastically over the past 20 years, would a 10-year or 20-year excess loss average be more appropriate? Click for Answer

A catastrophe model is a stochastic model that estimates the expected annual catastrophe loss based on an insurer's exposure. This amount is then added to the non-catastrophe expected loss to determine the aggregate expected loss used in a ratemaking analysis.

mini BattleQuiz 2 You must be logged in or this will not work.

Reinsurance

The topic of reinsurance has already been covered in Reserving Chapter 14 - Recoveries.

Adjustments to Losses: Coverage and Benefit Levels

The goal is to take losses from the historical experience period and restate them to what they would have been in the planned effective period. Recall that in chapter 5 we adjusted earned premiums for rate changes. Here, we adjust losses for benefit level changes. There are 3 methods for doing this:

- restate each individual claim from the current benefit level to the proposed benefit level (most accurate but has a high cost)

- restate groups of claims using average current and proposed benefit levels for each group (this is the method demonstrated here)

- computer simulation: generate simulated loss data under the proposed benefit conditions ← not discussed any further in source text

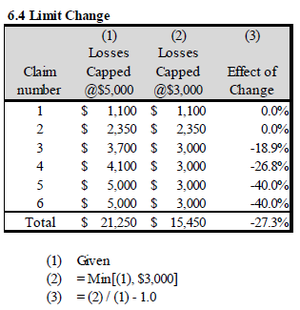

Method 1: (Restate individual claims.) Below is a simple example from the text where an insurer proposes reducing the coverage amount for jewelry, watches, and furs within a standard homeowners policy. The current coverage amount is $5,000 and the proposed amount is $3,000. We have loss amounts for 6 claims, originally capped at $5,000, now capped at $3,000. The aggregate percent change is calculated to be -27.3%. It is very accurate but requires access to individual claim records which can be costly and time-consuming.

The percent change of -27.3% is the direct effect of the coverage change. It assumes no change in policyholder behavior. Some policyholders however may want to retain the higher coverage level by purchasing a Personal Articles Floater (PAF). If the basic homeowners policy is secondary to the PAF, then homeowners losses would be reduced even further. This is an indirect effect. Pay attention to this. The concepts of direct and indirect effects have appeared on the exam. We'll discuss indirect effects in the next example in the context of benefit level changes for worker's compensation.

Method 2: (Restate groups of claims.) The basic version of this type of problem is confusing. That means you have to practice it more than certain other types of problems. It also has a very subtle element to it that is not explicitly discussed in the text but did come up on the 2017.Fall exam. We'll return to this further down. For now, just focus on the basic method for calculating the direct effect of the benefit level change. Here's the type of information you'd be typically be given for a worker's compensation example (WC).

Ok, the first thing you have to do is try to make sense of the data:

- The Statewide Average Weekly Wage, or SAWW, is easy. It's just the overall average pay for the group of workers in the entire program.

- For the table on the left, you have to understand what the ratio to SAWW means. If a particular worker has a wage of $1350 then their ratio to SAWW is 1350/1500 or 90%, putting them in the row labelled 75%-100%. They would be one of the 95 workers within that range of income, the total income for all those workers being $137,750. Maybe it's just me (and Alice) but using percentages seems like a strange way to label the rows. Why not denote the range with the equivalent dollar-values: 75% x $1500 = $1125 and 100% x $1500 = $1500. Anyway, the point is that however you do it, you have to subdivide the workers into a small number of groups; then do the math for the averages of each group. (This avoids the problem with Method 1 where you had to treat each claim individually.)

- The table on the right shows current and proposed percentages for 3 specific items, and this is the part I find the most confusing. The standard compensation rate of 80% of pre-injury wages is not changing - the current and proposed percentages are the same. The part that's changing is the increased minimum benefit (from 50% of SAWW to 75%) and the decreased maximum benefit (from 125% of SAWW to 100%). The solution shown below is not long, but it's easy to mess up. You have to be exceedingly careful to put these current and proposed percentages in all the correct places. The first few times you do this problem will be like following a recipe you don't understand. If you work slowly however, and think carefully about what you're doing, it will gradually make more sense.

Below is the solution but I suggest focusing first on step 3 because the formula for that step demonstrates clearly what you're trying to calculate. If you have total current benefits of $465,075 and total proposed benefits of $528,950 then the direct effect of the benefit level change is:

- → (total proposed benefit) / (total current benefit) – 1 = $528,950 / $465,075 – 1 = 13.7%

Now just fill in the details by working backwards through step 2 and then step 1. Of course when working these types of problems yourself you have to do the steps in order, but when you're learning it's often easier to see the bigger picture by starting at the end. (Shout-out to George Polya, famous mathematician, for writing the classic How to Solve It way back in 1944! Good problem-solving never goes out of style.)

| Alice's tips: The 4 values calculated in step 1 are used in step 2 to get columns (6) and (7). These columns are calculating the current and proposed benefits for each wage range. Both the current and proposed benefits are 80% of the pre-injury wage which would be easy to calculate, but the benefits are also subject to the given minimums and maximums. That's the part that makes it all so confusing. |

Here's a link to the exam problem similar to the above example as well as 4 similar practice problems. But before you jump in, remember I said this method has a very subtle element to it that is not explicitly discussed in the text but did come up on the 2017.Fall exam. If you want to read more about that click for Benefit Changes: Range Boundaries.

- E (2017.Fall #06)

Adjustments to Losses: Development

The development for estimating ultimate losses is discussed in detail in the reserving material in Reserving Chapter 7 - Development Method. Note that the pricing text refers to the development method as the chain ladder method.

Adjustments to Losses: Trending

Leveraged Effect of Limits

Overlap Fallacy

Loss Adjustment Expenses

POP QUIZ ANSWERS

Data Aggregation Example

Here's the summarized answer:

And here's the detailed explanation from the source text:

Pop Quiz A - Answer

- A 10-year average would be more appropriate because a 20-year average may understate the expected catastrophe potential given the increase in exposure.